For the last year, I’ve been working with City Springs Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore. Here’s a short description from the school’s website:

City Springs Elementary/Middle School is a neighborhood charter school operated by the Baltimore Curriculum Project (BCP). We are a conversion charter school, which means we were an already existing Baltimore City Public School that was taken over by an outside operator to bring innovative and research-based curriculum and other programs to enhance the school. To learn more about BCP, click here.

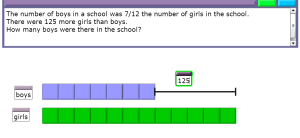

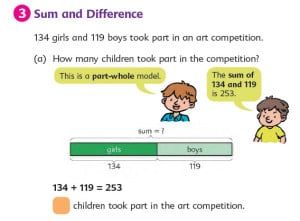

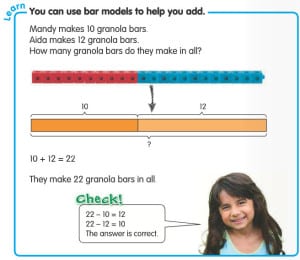

Initially, the school was seeking help with its Middle School math. After I made a pair of on-site visits at the end of the 2014-2015 school year, Dr. Rhonda Richetta, Principal of City Springs, decided to adopt Singapore’s Primary Mathematics Common Core Edition.

Initially, the school was seeking help with its Middle School math. After I made a pair of on-site visits at the end of the 2014-2015 school year, Dr. Rhonda Richetta, Principal of City Springs, decided to adopt Singapore’s Primary Mathematics Common Core Edition.

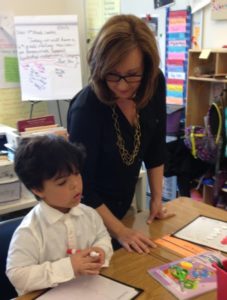

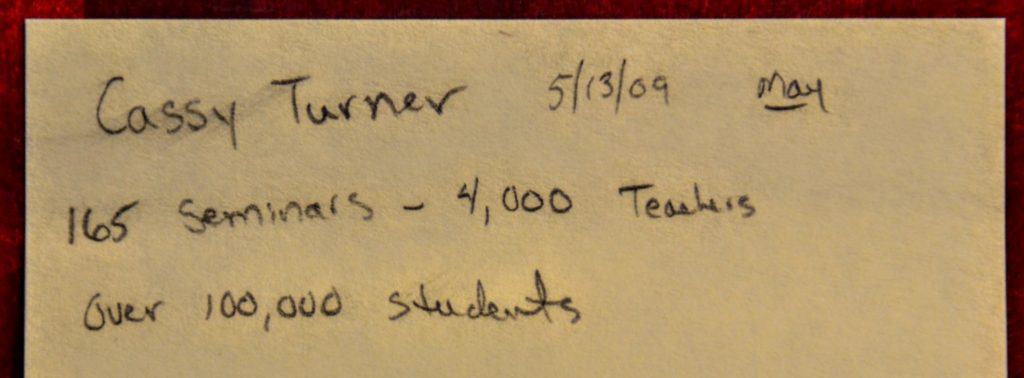

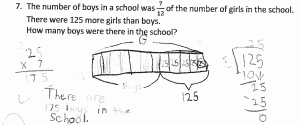

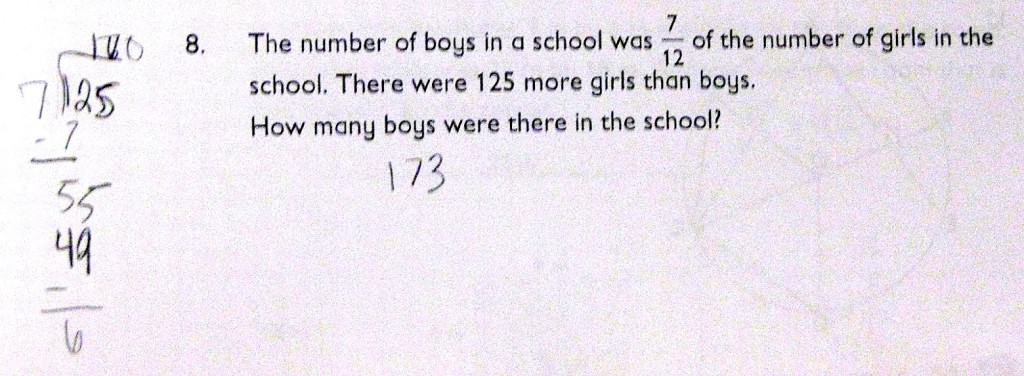

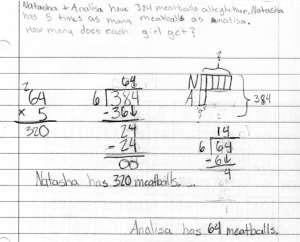

I’ve returned to City Springs periodically this year to provide continuing support as the school’s teachers and coaches adopted a Singapore Math® curriculum. The school is making remarkable progress, and I want to share stories written by some of City Springs’ dedicated teachers about the students’ growth during the year.

I’ve clipped an excerpt from each story with teachers’ observations and very valuable insights about the program and why it is working so well for their students. Please click on the links to read complete stories from the school’s website. I love the photos of students showing off their skills and having fun with math!

[Full disclosure: My work assignment at City Springs is contracted through Staff Development for Educators.]